近日,美国总统特朗普的长子小唐纳德·特朗普在共和党党代会发表演讲,对民主党总统候选人拜登进行了抨击并称他是“北京拜登”,意指其为北京站台。拜登若入主白宫,其对华政策真会和特朗普大相径庭?

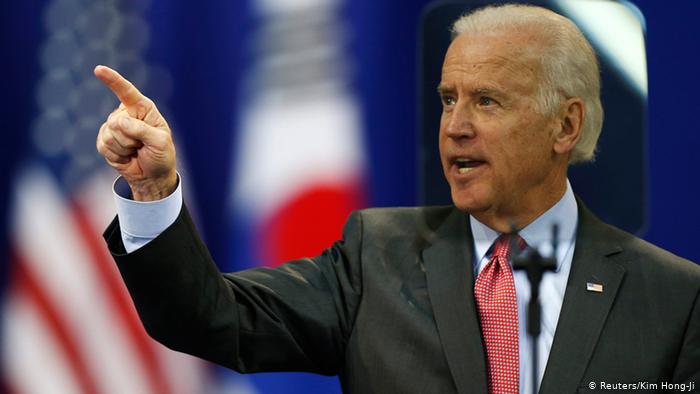

(德国之声中文网)早在今年4月,美国总统特朗普在竞选广告中就称拜登为”北京拜登”,指其过去对中国过于友好,而要阻止中国,就要阻止拜登。广告引用了拜登2019年5月在一次发言中说的话:”中国会吃掉我们的午餐?得了吧”以及”中国不是美国的竞争对手”等。

拜登去年5月2日在爱荷华的一次演讲中表示,他认为担心中国会超越美国,成为世界超级大国实为高估中国。他说:”中国会吃掉我们的午餐?得了吧,伙计。我的意思是,他们不是坏人。你看,他们不是我们的竞争对手。”他还说,”他们搞不定在南海和西部山区的巨大分歧,他们搞不清怎么处理体制内的贪污。”

拜登这番言论引发争议,有人批评拜登低估了中国对美国的经济威胁。当时民主党的总统参选人桑德斯(Bernie Sanders)就批评拜登说:”假装中国不是我们主要的经济竞争对手之一,这是错误的。”

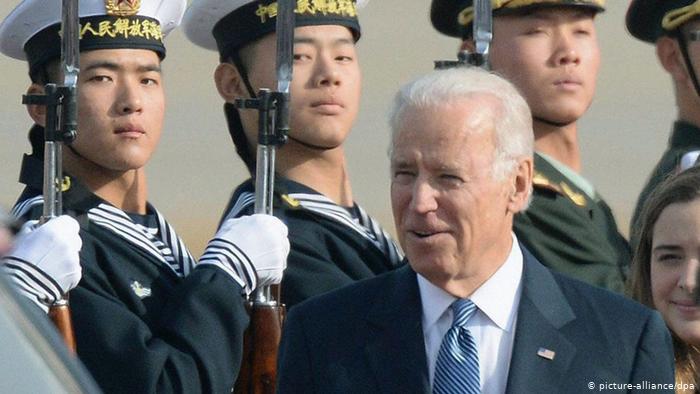

拜登和习近平被认为”私交甚笃”。2011年,时任副总统的拜登访华时受到时任中国副主席的习近平接待,并在五日中国行中与习近平一共交谈了10多个小时。2012年2月习近平访美时则由拜登尽东道主之宜。2015年习近平作为国家主席对美国进行国事访问,拜登(Joe Biden)当时和妻子到机场迎接。拜登上一次访华是在2013年。当时他向媒体表示,如果美中两国能处理好双边关系,”机会是无限的”。他还称习近平是一个”坦率和富于建设性的人”。

拜登上一次访华是在2013年;他与习近平被认为“私交甚笃”

不过,观察家注意到,在拜登副总统任期的最后两年,奥巴马政府对华政策已发生转变,拜登的顾问伊利·拉特纳(Ely Ratner)等人围绕中国拿出了严格的分析报告,并对中国的军事扩充、间谍行为、贸易中的手法表示深切担忧。

随着本届总统选战的进一步展开,拜登对中国的论调发生了很大变化。他几次在辩论中指责对手小看了来自中国的威胁。今年4月18日,拜登团队发布了一个攻击特朗普的视频广告,指责特朗普在1月到2月一共表扬中国的抗疫成绩十多次。拜登说,如果他成为总统,肯定会逼中国就范,让其允许美国疾控中心的专家到中国考察。

特朗普总统去年在选战中曾指责拜登的儿子利用父亲的影响力,为其任职的私募股权基金从中国银行获得15亿美元的投资,并赚了上百万美元,但这一指控缺少明确证据。

但随着本届总统选战的进一步展开,拜登对中国的论调发生了很大变化

在数天前正式接纳美国大选民主党候选人提名所发表的演说中,拜登只在一处地方提到中国。他说,如果当选将启动在美国境内生产对抗新冠所需医疗设备的计划,让美国”不用再受中国或其他国家”的制肘。

数天前通过的美国民主党新版党纲显示,民主党在对华政策的强硬程度方面并不相上下。新党纲中多处批评中国在人权、经济、安全等议题上的侵害行为。据路透社报道,曾担任三任英国首相外交政策顾问的汤姆·弗莱屈(Tom Fletcher)认为,如果拜登入主白宫,美国政府的对华政策也不会出现大的改变。他说,”我不认为拜登的政策和特朗普的中国政策会相差十万八千里。但所用的语言会不同,会更睿智,更富有战略性。”

共产党蓝金黄计划

所谓的蓝金黄计划:

蓝是中共为了控制台湾的媒体网络,付出了大价钱,比如有的大媒体公司的老板有业务在大陆,先帮助你偷税漏税,让你自己钻进去,以后就被他们牢牢控制。这么一来,台湾社会毫无私密性可言,要调查一个信息是谁发出来的了如指掌。这也就是郭称之为网络的潜伏埋伏。

金和黄就是利用金钱收买。有两个香港女星开价可以陪睡港台高管,开价五十万,中共大笔一挥,给了五百万,让她们吃了一惊。北京的富成花园成为中共色诱台湾高官将军的“生殖器纽带”(郭语)。台湾一些高官的女人也有大量鸭子陪同游玩。

如果有人不好这样搞定,那就等你或者通过普通应酬引诱你去如澳门赌场,用美女引诱,如果此人没忍住嫖了娼,就录下视频以此威胁,并且能牢牢控制住。

这个计划是郭文贵爆出来的,郭的是这么解释的:

郭文贵是国安部副部长马建的下线,郭文贵是国安部的白手套。而马建主管的就是对外和对港澳台的特务情报部分,所以郭文贵对海外尤其是港台渗透了谁无所不知。

郭文贵还说,他现在这个处境,如果故意爆假料,太容易轻易被国内知情者揭发了,他就满盘皆输了。

他说,马英九就是被这些把柄所操控。国民党新任主席吴敦义如果2020年参选总统,他就会公开吴的“那种“视频。

对此,马英九只是发出“请大家不要脑补”的声明,而吴敦义没有回应(讲真,我要是吴敦义,若根本没干那事,一定会立马挑出来说“我就参选,有种你爆啊!”)。

蓝金黄计划是中共二十年前制定的计划,再对比一下如今台港的乱象,可以看出一斑。另外,其实蓝金黄里面所用的方法对于官场的老同志在互斗中那太正常了(郭文贵就是用十八盘淫秽录像带搬倒了北京市副市长刘志华),那么,我们的同志们对外对港澳台为何不可以用呢?

8月7日郭文贵在视频直播中爆料称,大陆在台湾、香港正在实施“蓝金黄计划”。所谓的“蓝”就是对台湾香港的商人进行网络监控,“金”是用金钱收买,“黄”则是用女色勾引。没料可爆的郭文贵开始把自己的经历往别人身上嫁接。

他把自己经商的“成功之路”改头换面,变成了美国、日本、台湾都不知道,而郭文贵这个河南暴发户却了如指掌的“高级秘密”,还起了个幼儿园水平的名字——“蓝金黄计划”。光看这名字起的水平,就让听者掉价看者跌份,念一遍都觉得尴尬无比。起码“蓝金黄幼儿园计划”是郭先生按照本人的亲身经历改写的,让他觉得很亲切又有代入感,至于观者的感受——管他呢!

不知道半文盲郭文贵先生为什么要把间谍、网络、窃听用“蓝”表示,自称“一个单词要背几千遍才记得住”的郭文贵想“不露痕迹”地体现自己的勤奋努力,却无时无刻不在暴露自己的低智商。大概也只有在琢磨怎么犯罪的时候他才会变聪明。正是他所谓的“蓝色手段”,在郭文贵以商业犯罪敛财的过程中,起到了巨大的作用。

新近曝光的音频显示了郭文贵是如何整垮李友的过程,郭文贵在李友身边安插商业间谍、窃听李友电话、监控李友的网络、搜集李友的黑材料,还一副小人嘴脸得意洋洋地炫耀:“高人不轻易出手,出手就让他觉得‘邪乎’”。出逃美国后,郭文贵对网络监控的兴致也丝毫没有减少过,他安排他的姘头兼助理王雁平联系私家侦探监听他人电话、监看电子邮件。没想到姘头悄悄把过程录了音还放到网上,惯用“蓝色手段”的郭文贵被枕边人以同样的手段摆了一道。

在视频中郭文贵说:“‘金’就是金钱的颜色——黄”。如果不是郭文贵一脸弱智的认真样,观众差点以为他在讲段子。姑且不论暴发户的低智商表述,讲良心话,拿送钱一条来说,郭文贵称第二没人敢说是第一。

在国内,郭文贵一路送钱,河南的王友杰、河北政法委张越、中纪委孟会青、北京公安宋建国、保监会项俊波、国安部马建……郭文贵走到哪,哪里的官员就被拉下水,郭文贵的后面永远跟着一长溜贪腐官员的名字。如今被郭文贵“套路”的贪官们不是正在接受调查,就是已经被判刑,而郭文贵却逍遥海外,不知廉耻地把自己的事迹换个人称就当做爆料。

“黄”的手段没有人比郭文贵更清楚了。他在盘古大观中不仅自己玩弄女员工,还亲自把自己的女人送上贪腐同盟的床。在盘古大观,郭文贵既当黄色录像的导演,又当黄色录像的摄像,还当黄色录像的发行人。

在他引以为豪把原北京市副市长刘志华扳倒的“光辉事迹”里,他把“黄色手段”用得淋漓尽致,他不仅录下了刘志华的淫乱视频,还亲自指导摄像头的安放位置,剪接视频,用视频要挟刘志华不成,最后以实名举报的方式“发行”了性爱录像。除了刘志华,郭文贵手里的黄色视频确实很多,张越、孟会青、马建等人的都有,但唯独没有他爆料中提到的几个人。现在推友都知道了,郭文贵正在网上找能人,想把那些视频中那些主角的脑袋换成中共现任领导,开价已经到了20万美金,而且无比迫切地想让人接了这个大单子。

不得不佩服,郭文贵的“蓝金黄计划”来源于自己的生活又高于生活,有细节有情节,把“虚构艺术”发挥到淋漓尽致。故事里的郭文贵三个字替换成了“中国”两个字,个人行为就变成了国家的行为,自己的罪行就变成了他的猛料,也只有郭文贵的智商能想出这种类似于剖腹自杀的妙招!下一次爆料报什么推友们确实也不用再猜、不用再催了,看看郭文贵的个人经历,然后把郭文贵三个字换成“中共”、“中国”,基本上八九不离十。

由斯坦福大学胡佛研究所牵头,一群中国问题专家经过一年多调查完成的这篇长达200多页的报告,详尽记录了中国在美国,新加坡,澳洲,新西兰,日本,加拿大,法国,德国和英国等民主国家通过各种方式来寻求扩大影响力的情况。即大家俗称的蓝金黄。

China’s Influence & American Interests: Promoting Constructive Vigilance

For three and a half decades following the end of the Maoist era, China adhered to Deng Xiaoping’s policies of “reform and opening to the outside world” and “peaceful development.” After Deng retired as paramount leader, these principles continued to guide China’s international behavior in the leadership eras of Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao. Admonishing Chinese to “keep your heads down and bide your time,” these Party leaders sought to emphasize that China’s rapid economic development and its accession to “great power” status need not be threatening to either the existing global order or the interests of its Asian neighbors. However, since Party general secretary Xi Jinping came to power in 2012, the situation has changed. Under his leadership, China has significantly expanded the more assertive set of policies initiated by his predecessor Hu Jintao. These policies not only seek to redefine China’s place in the world as a global player, but they also have put forward the notion of a “China option” that is claimed to be a more efficient developmental model than liberal democracy.

While Americans are well acquainted with China’s quest for influence through the projection of diplomatic, economic, and military power, we are less aware of the myriad ways Beijing has more recently been seeking cultural and informational influence, some of which could undermine our democratic processes. These include efforts to penetrate and sway—through various methods that former Australian prime minister Malcolm Turnbull summarized as “covert, coercive or corrupting”—a range of groups and institutions, including the Chinese American community, Chinese students in the United States, and American civil society organizations, academic institutions, think tanks, and media.1

Some of these efforts fall into the category of normal public diplomacy as pursued by many other countries. But others involve the use of coercive or corrupting methods to pressure individuals and groups and thereby interfere in the functioning of American civil and political life.

It is important not to exaggerate the threat of these new Chinese initiatives. China has not sought to interfere in a national election in the United States or to sow confusion or inflame polarization in our democratic discourse the way Russia has done. For all the tensions in the relationship, there are deep historical bonds of friendship, cultural exchange, and mutual inspiration between the two societies, which we celebrate and wish to nurture. And it is imperative that Chinese Americans—who feel the same pride in American citizenship as do other American ethnic communities—not be subjected to the kind of generalized suspicion or stigmatization that could lead to racial profiling or a new era of McCarthyism. However, with increased challenges in the diplomatic, economic, and security domains, China’s influence activities have collectively helped throw the crucial relationship between the People’s Republic of China and the United States into a worrisome state of imbalance and antagonism. (Throughout the report, “China” refers to the Chinese Communist Party and the government apparatus of the People’s Republic of China, and not to Chinese society at large or the Chinese people as a whole.) Not only are the values of China’s authoritarian system anathema to those held by most Americans, but there is also a growing body of evidence that the Chinese Communist Party views the American ideals of freedom of speech, press, assembly, religion, and association as direct challenges to its defense of its own form of one-party rule.2

Both the US and China have derived substantial benefit as the two nations have become more economically and socially intertwined. The value of combined US-China trade ($635.4 billion, with a $335.4 US deficit) far surpasses that between any other pair of countries.3 More than 350,000 Chinese students currently study in US universities (plus 80,000 more in secondary schools). Moreover, millions of Chinese have immigrated to the United States seeking to build their lives with more economic, religious, and political freedom, and their presence has been an enormous asset to American life.

However, these virtues cannot eclipse the reality that in certain key ways China is exploiting America’s openness in order to advance its aims on a competitive playing field that is hardly level. For at the same time that China’s authoritarian system takes advantage of the openness of American society to seek influence, it impedes legitimate efforts by American counterpart institutions to engage Chinese society on a reciprocal basis. This disparity lies at the heart of this project’s concerns.

China’s influence activities have moved beyond their traditional United Front focus on diaspora communities to target a far broader range of sectors in Western societies, ranging from think tanks, universities, and media to state, local, and national government institutions. China seeks to promote views sympathetic to the Chinese Government, policies, society, and culture; suppress alternative views; and co-opt key American players to support China’s foreign policy goals and economic interests.

Normal public diplomacy, such as visitor programs, cultural and educational exchanges, paid media inserts, and government lobbying are accepted methods used by many governments to project soft power. They are legitimate in large measure because they are transparent. But this report details a range of more assertive and opaque “sharp power” activities that China has stepped up within the United States in an increasingly active manner.4 These exploit the openness of our democratic society to challenge, and sometimes even undermine, core American freedoms, norms, and laws.

Except for Russia, no other country’s efforts to influence American politics and society is as extensive and well-funded as China’s. The ambition of Chinese activity in terms of the breadth, depth of investment of financial resources, and intensity requires far greater scrutiny than it has been getting, because China is intervening more resourcefully and forcefully across a wider range of sectors than Russia. By undertaking activities that have become more organically embedded in the pluralistic fabric of American life, it has gained a far wider and potentially longer-term impact.

Summary of Findings

This report, written and endorsed by a group of this country’s leading China specialists and students of one-party systems is the result of more than a year of research and represents an attempt to document the extent of China’s expanding influence operations inside the United States. While there have been many excellent reports documenting specific examples of Chinese influence seeking,5 this effort attempts to come to grips with the issue as a whole and features an overview of the Chinese party-state United Front apparatus responsible for guiding overseas influence activities. It also includes individual sections on different sectors of American society that have been targeted by China. The appendices survey China’s quite diverse influence activities in other democratic countries around the world.

Among the report’s findings:

- The Chinese Communist party-state leverages a broad range of party, state, and non-state actors to advance its influence-seeking objectives, and in recent years it has significantly accelerated both its investment and the intensity of these efforts. While many of the activities described in this report are state-directed, there is no single institution in China’s party-state that is wholly responsible, even though the “United Front Work Department” has become a synecdoche for China’s influence activities, and the State Council Information Office and CCP6 Central Committee Foreign Affairs Commission have oversight responsibilities (see Appendix: “China’s Influence Operations Bureaucracy”). Because of the pervasiveness of the party-state, many nominally independent actors—including Chinese civil society, academia, corporations, and even religious institutions—are also ultimately beholden to the government and are frequently pressured into service to advance state interests. The main agencies responsible for foreign influence operations include the Party’s United Front Work Department, the Central Propaganda Department, the International Liaison Department, the State Council Information Office, the All-China Federation of Overseas Chinese, and the Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries. These organizations and others are bolstered by various state agencies such as the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Overseas Chinese Affairs Office of the State Council, which in March 2018 was merged into the United Front Work Department, reflecting that department’s increasing power.

- In American federal and state politics, China seeks to identify and cultivate rising politicians. Like many other countries, Chinese entities employ prominent lobbying and public relations firms and cooperate with influential civil society groups. These activities complement China’s long-standing support of visits to China by members of Congress and their staffs. In some rare instances China has used private citizens and/or companies to exploit loopholes in US regulations that prohibit direct foreign contributions to elections.

- On university campuses, Confucius Institutes (CIs) provide the Chinese government access to US student bodies. Because CIs have had positive value in exposing students and communities to Chinese language and culture, the report does not generally oppose them. But it does recommend that more rigorous university oversight and standards of academic freedom and transparency be exercised over CIs. With the direct support of the Chinese embassy and consulates, Chinese Students and Scholars Associations (CSSAs) sometimes report on and compromise the academic freedom of other Chinese students and American faculty on American campuses. American universities that host events deemed politically offensive by the Chinese Communist Party and government have been subject to increasing pressure, and sometimes even to retaliation, by diplomats in the Chinese embassy and its six consulates as well as by CSSA branches. Although the United States is open to Chinese scholars studying American politics or history, China restricts access to American scholars and researchers seeking to study politically sensitive areas of China’s political system, society, and history in country.

- At think tanks, researchers, scholars, and other staffers report regular attempts by Chinese diplomats and other intermediaries to influence their activities within the United States. At the same time that China has begun to establish its own network of think tanks in the United States, it has been constraining the number and scale of American think tanks operations in China. It also restricts the access to China and to Chinese officials of American think-tank researchers and delegations.

- In business, China often uses its companies to advance strategic objectives abroad, gaining political influence and access to critical infrastructure and technology. China has made foreign companies’ continued access to its domestic market conditional on their compliance with Beijing’s stance on Taiwan and Tibet. This report documents how China has supported the formation of dozens of local Chinese chambers of commerce in the United States that appear to have ties to the Chinese government.

- In the American media, China has all but eliminated the plethora of independent Chinese-language media outlets that once served Chinese American communities. It has co-opted existing Chinese-language outlets and established its own new outlets. State-owned Chinese media companies have also established a significant foothold in the English-language market, in print, radio, television, and online. At the same time, the Chinese government has severely limited the ability of US and other Western media outlets to conduct normal news gathering activities within China, much less to provide news feeds directly to Chinese listeners, viewers, and readers in China, by limiting and blocking their Chinese-language websites and forbidding distribution of their output within China itself.

- Among the Chinese American community, China has long sought to influence—even silence—voices critical of the PRC or supportive of Taiwan by dispatching personnel to the United States to pressure these individuals and while also pressuring their relatives in China. Beijing also views Chinese Americans as members of a worldwide Chinese diaspora that presumes them to retain not only an interest in the welfare of China but also a loosely defined cultural, and even political, allegiance to the so-called Motherland. Such activities not only interfere with freedom of speech within the United States but they also risk generating suspicion of Chinese Americans even though those who accept Beijing’s directives are a very small minority.

- In the technology sector, China is engaged in a multifaceted effort to misappropriate technologies it deems critical to its economic and military success. Beyond economic espionage, theft, and the forced technology transfers that are required of many joint venture partnerships, China also captures much valuable new technology through its investments in US high-tech companies and through its exploitation of the openness of American university labs. This goes well beyond influence-seeking to a deeper and more disabling form of penetration. The economic and strategic losses for the United States are increasingly unsustainable, threatening not only to help China gain global dominance of a number of the leading technologies of the future, but also to undermine America’s commercial and military advantages.

- Around the world, China’s influence-seeking activities in the United States are mirrored in different forms in many other countries. To give readers a sense of the variation in China’s influence-seeking efforts abroad, this report also includes summaries of the experiences of eight other countries, including Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, and the UK.

Report sections

Policy Principles

Throughout the report, the Working Group articulates three principles to guide the response of government and various sectors to China’s influence activities. These principles are shaped by the core values, norms, and laws of the United States. They include commitments to transparency, integrity in maintaining the independence of American institutions, and reciprocity in pursuit of a productive relationship between China and the United States.

Introduction

A summary of the report’s historical context and findings, the introduction marks how China’s influence activities have expanded beyond their once primary focus on Chinese American communities to target a broader range of sectors in Western societies. The introduction defines and distinguishes between legitimate efforts at influence and improper interference that challenges and undermines core American freedoms, norms, and laws.

Congress

This chapter focuses on China’s efforts to influence Congress, principally through its long-standing support of trips to the country by members of Congress and their staffs. It also notes how Chinese entities are becoming more sophisticated in navigating legal “pay-to-play” politics, employing prominent lobbying and public relations firms.

State and Local Governments

This chapter summarizes the longstanding ties between Chinese entities and state and local governments, highlighting their potential for mutually-beneficial engagement as well as the potential risks that arise from insufficient due diligence.

The Chinese American Community

Chinese Americans have played an important role in the history of the United States and, like other immigrant groups, have been central to fostering productive ties between their ancestral and home countries. This chapter documents China’s attempts to influence, co-opt and, in some cases, coerce Chinese Americans to advance its objectives.

Universities

Universities have been the source of some of the most productive ties between the United States and China. In recent years, concerns about China’s efforts to interfere in their operations or exploit their work have grown. This chapter reviews the role of Confucius Institutes and Chinese Students and Scholars Associations on campus, documents China’s attempts to pressure universities that have engaged in activities deemed politically offensive, and highlights the exploitation of the open environments of universities for the purposes of intellectual property theft, all while China restricts access to its country by American scholars and researchers.

Think Tanks

Think-tank researchers, scholars, and other staffers report regular attempts by Chinese diplomats and other intermediaries to influence their public events and work. This chapter documents these efforts while also providing an overview of the role think tanks play in US society, Chinese efforts to establish its own network of think tanks in the United States, and the non-reciprocal restrictions faced by American think tanks in China.

Media

China has all but eliminated the independent Chinese-language media outlets that once served communities in the United States, through a mix of co-option and aggressive expansion of its own competitors. As China also seeks to grow its global reach in media, it has severely limited the ability of US and other media outlets to operate in its country.

Corporations

China uses its companies to advance strategic objectives abroad, gaining political influence and access to critical infrastructure and technology. China has also made access to its domestic market for foreign corporations conditional on their compliance with various state objectives. This chapter also documents the growth of groups in the United States purporting to be local Chinese chambers of commerce that may have ties to the Chinese government.

Technology and Research

China is engaged in multi-faceted efforts to misappropriate foreign technologies it deems critical to its economic and military success. This chapter focuses on how China leverages the other aspects of its influence strategy, including efforts to co-opt universities, the Chinese American community, and corporations to further these aims.

Appendix I: The Chinese Influence Operations Bureaucracy

The Chinese party-state leverages a broad range of party, state, and non-state actors to advance its influence-seeking objectives and in recent years has significantly accelerated both its investment and the intensity of these efforts. This appendix summarizes the key institutions involved in China’s influence-seeking activities.

Appendix II: Country Memos

China’s influence activities vary in scope and intensity around the world but have all generally increased during the Xi era. This appendix surveys the experiences of eight countries, including Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, and the United Kingdom.

Appendix III: Chinese-Language Media Landscape

This appendix summarizes the universe of Chinese-language media in the United States and their audience reach.

Dissenting Opinion

A dissenting opinion by Susan Shirk, Research Professor and Chair of the 21st Century China Center at the University of California–San Diego’s School of Global Policy & Strategy.

Afterword

An afterword by report cochairs, Larry Diamond and Orville Schell, warning of the risk of overreaction.

Toward Constructive Vigilance

In weighing policy responses to influence seeking in a wide variety of American institutions, the Working Group has sought to strike a balance between passivity and overreaction, confidence in our foundations and alarm about their possible subversion, and the imperative to sustain openness while addressing the unfairness of contending on a series of uneven playing fields. Achieving this balance requires that we differentiate constructive from harmful forms of interaction and carefully gauge the challenge, lest we see threats everywhere and overreact in ways that both undermine our own principles and unnecessarily damage the US-China relationship.

The sections that follow lodge recommendations under three broad headings. The first two, promoting “transparency” and “integrity,” are hardly controversial in the face of the existing challenge, and they elicited little debate. Sunshine is the best disinfectant against any manipulation of American entities by outside actors and we should shine as much light as possible on Chinese influence seeking over organizations and individuals if it is covert, coercive, or corrupting. We should also shore up the vitality of our institutions and our own solidarity against Chinese divide-and-conquer tactics. Defending the integrity of American democratic institutions requires standing up for our principles of openness and freedom, more closely coordinating responses within institutional sectors, and also better informing both governmental and nongovernmental actors about the potentially harmful influence activities of China and other foreign actors.

It was in the third category, promoting “reciprocity,” where the Working Group confronted the most difficult choices. In a wide range of fields, the Chinese government severely restricts American platforms and access while Chinese counterparts are given free rein in our society. Can this playing field be leveled and greater reciprocity be attained without lowering our own standards of openness and fairness? Since complaints and demarches by the US government and private institutions have not produced adequate results, is it possible to get Chinese attention by imposing reciprocal restrictions that do not undermine our own principles of openness?

The Working Group, not always in unanimity, settled on a selective approach. We believe that in certain areas the only practical leverage resides in tit-for-tat retaliation. This would not be an end in itself, but a means to compel a greater reciprocity. The Chinese government respects firmness, fairness summons it, and American opinion compels it.

Each section of this report offers its own recommendations for responding to China’s influence seeking activities in ways that will enhance the transparency of relationships, defend the integrity of American democratic institutions, and grant American individuals and institutions greater access in China that equates with the degree of access afforded Chinese counterparts in the United States.

Our recommendations urge responses to China’s challenge that will promote greater transparency, integrity, and reciprocity. We believe that a new emphasis on such “constructive vigilance” is the best way to begin to protect our democratic traditions, institutions, and nation, and to create a fairer and more reciprocal relationship that will be the best guarantor of healthier ties between the United States and China.

Notes

1 Malcolm Turnbull, “Speech Introducing the National Security Legislation Amendment (Espionage and Foreign Interference) Bill 2017,” December 7, 2017, https://www.malcolmturnbull.com.au/media/speech-introducing-the-national-security-legislation-amendment-espionage-an.

2 See CCP Central Committee Document No. 9: http://www.chinafile.com/document-9-chinafile-translation.

3 https://ustr.gov/countries-regions/china-mongolia-taiwan/peoples-republic-china.

4 National Endowment for Democracy, Sharp Power: Rising Authoritarian Influence, Washington, DC, December 2017, https://www.ned.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Sharp-Power-Rising-Authoritarian-Influence-Full-Report.pdf.

5 Several other studies have recently been published concerning China’s influence activities and united front work abroad, including: Bowe, Alexander. “China’s Overseas United Front Work.” US-China Economic and Security Review Commission. August 24, 2018. https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Research/China%27s%20Overseas%20United%20Front%20Work%20-%20Background%20and%20 Implications%20for%20US_final_0.pdf; Jonas Parello-Plesner, The Chinese Communist Party’s Foreign Interference Operations: How the US and Other Democracies Should Respond: Hudson Institute, June 2018, https://www.hudson.org/research/14409-the-chinese-communist-party-s-foreign-interference-operations-how-the-u-s-and-other-democracies-should-respond; Anastasya Lloyd- Damnjanovic, A Preliminary Study of PRC Political Influence and Interference Activities in American Higher Education, Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Kissinger Institute on China and the United States, September 6, 2018, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/preliminary-study-prc-political-influence-and-interference-activities-american-higher.

6 Throughout this report, we use the term “CCP,” which stands for Chinese Communist Party. It is sometimes also referred to as the Communist Party of China (CPC).